#1: Value Investing isn’t Easy

Value investing requires a great deal of hard work, unusually strict discipline, and a long-term investment horizon. Few are willing and able to devote sufficient time and effort to become value investors, and only a fraction of those have the proper mindset to succeed.

Like most eighth- grade algebra students, some investors memorize a few formulas or rules and superficially appear competent but do not really understand what they are doing. To achieve long-term success over many financial market and economic cycles, observing a few rules is not enough.

Too many things change too quickly in the investment world for that approach to succeed. It is necessary instead to understand the rationale behind the rules in order to appreciate why they work when they do and don’t when they don’t. Value investing is not a concept that can be learned and applied gradually over time. It is either absorbed and adopted at once, or it is never truly learned.

Value investing is simple to understand but difficult to implement. Value investors are not super-sophisticated analytical wizards who create and apply intricate computer models to find attractive opportunities or assess underlying value.

The hard part is discipline, patience, and judgment. Investors need discipline to avoid the many unattractive pitches that are thrown, patience to wait for the right pitch, and judgment to know when it is time to swing.

#2: Being a Value Investor

The disciplined pursuit of bargains makes value investing very much a risk-averse approach. The greatest challenge for value investors is maintaining the required discipline.

Being a value investor usually means standing apart from the crowd, challenging conventional wisdom, and opposing the prevailing investment winds. It can be a very lonely undertaking.

A value investor may experience poor, even horrendous, performance compared with that of other investors or the market as a whole during prolonged periods of market overvaluation. Yet over the long run the value approach works so successfully that few, if any, advocates of the philosophy ever abandon it.

#3: An Investor’s Worst Enemy

If investors could predict the future direction of the market, they would certainly not choose to be value investors all the time. Indeed, when securities prices are steadily increasing, a value approach is usually a handicap; out- of-favor securities tend to rise less than the public’s favorites. When the market becomes fully valued on its way to being overvalued, value investors again fare poorly because they sell too soon.

The most beneficial time to be a value investor is when the market is falling. This is when downside risk matters and when investors who worried only about what could go right suffer the consequences of undue optimism. Value investors invest with a margin of safety that protects them from large losses in declining markets.

Those who can predict the future should participate fully, indeed on margin using borrowed money, when the market is about to rise and get out of the market before it declines. Unfortunately, many more investors claim the ability to foresee the market’s direction than actually possess that ability. (I myself have not met a single one.)

Those of us who know that we cannot accurately forecast security prices are well advised to consider value investing, a safe and successful strategy in all investment environments.

#4: It’s All about the Mindset

Investment success requires an appropriate mindset.

Investing is serious business, not entertainment. If you participate in the financial markets at all, it is crucial to do so as an investor, not as a speculator, and to be certain that you understand the difference.

Needless to say, investors are able to distinguish Pepsico from Picasso and understand the difference between an investment and a collectible.

When your hard-earned savings and future financial security are at stake, the cost of not distinguishing is unacceptably high.

#5: Don’t Seek Mr. Market’s Advice

Some investors – really speculators – mistakenly look to Mr. Market for investment guidance.

They observe him setting a lower price for a security and, unmindful of his irrationality, rush to sell their holdings, ignoring their own assessment of underlying value. Other times they see him raising prices and, trusting his lead, buy in at the higher figure as if he knew more than they.

The reality is that Mr. Market knows nothing, being the product of the collective action of thousands of buyers and sellers who themselves are not always motivated by investment fundamentals.

Emotional investors and speculators inevitably lose money; investors who take advantage of Mr. Market’s periodic irrationality, by contrast, have a good chance of enjoying long-term success.

#6: Stock Price Vs Business Reality

Louis Lowenstein has warned us not to confuse the real success of an investment with its mirror of success in the stock market.

The fact that a stock price rises does not ensure that the underlying business is doing well or that the price increase is justified by a corresponding increase in underlying value. Likewise, a price fall in and of itself does not necessarily reflect adverse business developments or value deterioration.

It is vitally important for investors to distinguish stock price fluctuations from underlying business reality. If the general tendency is for buying to beget more buying and selling to precipitate more selling, investors must fight the tendency to capitulate to market forces.

You cannot ignore the market – ignoring a source of investment opportunities would obviously be a mistake but you must think for yourself and not allow the market to direct you.

#7: Price Vs Value

Value in relation to price, not price alone, must determine your investment decisions.

If you look to Mr. Market as a creator of investment opportunities (where price departs from underlying value), you have the makings of a value investor.

If you insist on looking to Mr. Market for investment guidance, however, you are probably best advised to hire someone else to manage your money.

Because security prices can change for any number of reasons and because it is impossible to know what expectations are reflected in any given price level, investors must look beyond security prices to underlying business value, always comparing the two as part of the investment process.

#8: Emotions Play Havoc in Investing

Unsuccessful investors are dominated by emotion. Rather than responding coolly and rationally to market fluctuations, they respond emotionally with greed and fear.

We all know people who act responsibly and deliberately most of the time but go berserk when investing money. It may take them many months, even years, of hard work and disciplined saving to accumulate the money but only a few minutes to invest it.

The same people would read several consumer publications and visit numerous stores before purchasing a stereo or camera yet spend little or no time investigating the stock they just heard about from a friend.

Rationality that is applied to the purchase of electronic or photographic equipment is absent when it comes to investing.

#9: Stock Market ≠ Quick Money

Many unsuccessful investors regard the stock market as a way to make money without working rather than as a way to invest capital in order to earn a decent return.

Anyone would enjoy a quick and easy profit, and the prospect of an effortless gain incites greed in investors. Greed leads many investors to seek shortcuts to investment success.

Rather than allowing returns to compound over time, they attempt to turn quick profits by acting on hot tips. They do not stop to consider how the tipster could possibly be in possession of valuable information that is not illegally obtained or why, if it is so valuable, it is being made available to them.

Greed also manifests itself as undue optimism or, more subtly, as complacency in the face of bad news.

Finally greed can cause investors to shift their focus away from the achievement of long-term investment goals in favor of short-term speculation.

#10: Stock Market Cycles

All market fads come to an end. Security prices eventually become too high, supply catches up with and then exceeds demand, the top is reached, and the downward slide ensues.

There will always be cycles of investment fashion and just as surely investors who are susceptible to them.

It is only fair to note that it is not easy to distinguish an investment fad from a real business trend. Indeed, many investment fads originate in real business trends, which deserve to be reflected in stock prices.

The fad becomes dangerous, however, when share prices reach levels that are not supported by the conservatively appraised values of the underlying businesses.

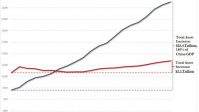

#11: How Big Investors Misbehave and Why They Underperform

If the behavior of institutional investors weren’t so horrifying, it might actually be humorous.

Hundreds of billions of other people’s hard-earned dollars are routinely whipped from investment to investment based on little or no in-depth research or analysis.

The prevalent mentality is consensus, groupthink. Acting with the crowd ensures an acceptable mediocrity;

acting independently runs the risk of unacceptable underperformance.

Indeed, the short-term, relative-performance orientation of many money managers has made “institutional investor” a contradiction in terms.

Most money managers are compensated, not according to the results they achieve, but as a percentage of the total assets under management. The incentive is to expand managed assets in order to generate more fees. Yet while a money management business typically becomes more profitable as assets under management increase, good investment performance becomes increasingly difficult.

This conflict between the best interests of the money manager and that of the clients is typically resolved in the manager’s favor.

#12: Short-Term, Relative-Performance Derby

Like dogs chasing their own tails, most institutional investors have become locked into a short-term, relative- performance derby. Fund managers at one institution have suffered the distraction of hourly performance calculations; numerous managers are provided daily comparisons of their results with those of managers at other firms.

Frequent comparative ranking can only reinforce a short-term investment perspective.

It is understandably difficult to maintain a long-term view when, faced with the penalties for poor short-term performance, the long- term view may well be from the unemployment line.

Investing without understanding the behavior of institutional investors is like driving in a foreign land without a map. You may eventually get where you are going, but the trip will certainly take longer, and you risk getting lost

along the way.

#13: First, Avoid Losses

Warren Buffett likes to say that the first rule of investing is “Don’t lose money,” and the second rule is, “Never forget the first rule.”

I too believe that avoiding loss should be the primary goal of every investor. This does not mean that investors should never incur the risk of any loss at all. Rather “don’t lose money” means that over several years an investment portfolio should not be exposed to appreciable loss of principal.

While no one wishes to incur losses, you couldn’t prove it from an examination of the behavior of most investors and speculators. The speculative urge that lies within most of us is strong; the prospect of a free lunch can be compelling, especially when others have already seemingly partaken.

It can be hard to concentrate on potential losses while others are greedily reaching for gains and your broker is on the phone offering shares in the latest “hot” initial public offering. Yet the avoidance of loss is the surest way to ensure a profitable outcome.

#14: Relevance of Temporary Price Fluctuations

In addition to the probability of permanent loss attached to an investment, there is also the possibility of interim price fluctuations that are unrelated to underlying value.

Many investors consider price fluctuations to be a significant risk: if the price goes down, the investment is seen as risky regardless of the fundamentals.

But are temporary price fluctuations really a risk? Not in the way that permanent value impairments are and then only for certain investors in specific situations.

It is, of course, not always easy for investors to distinguish temporary price volatility, related to the short-term forces of supply and demand, from price movements related to business fundamentals. The reality may only become apparent after the fact.

While investors should obviously try to avoid overpaying for investments or buying into businesses that subsequently decline in value due to deteriorating results, it is not possible to avoid random short-term market volatility. Indeed, investors should expect prices to fluctuate and should not invest in securities if they cannot tolerate some volatility.

If you are buying sound value at a discount, do short-term price fluctuations matter? In the long run they do not matter much; value will ultimately be reflected in the price of a security. Indeed, ironically, the long-term investment implication of price fluctuations is in the opposite direction from the near-term market impact.

For example, short-term price declines actually enhance the returns of long-term investors. There are, however, several eventualities in which near-term price fluctuations do matter to investors. Security holders who need to sell in a hurry are at the mercy of market prices. The trick of successful investors is to sell when they want to, not when they have to.

Near-term security prices also matter to investors in a troubled company. If a business must raise additional capital in the near term to survive, investors in its securities may have their fate determined, at least in part, by the prevailing market price of the company’s stock and bonds.

The third reason long-term-oriented investors are interested in short-term price fluctuations is that Mr. Market can create very attractive opportunities to buy and sell. If you hold cash, you are able to take advantage of such opportunities. If you are fully invested when the market declines, your portfolio will likely drop in value, depriving you of the benefits arising from the opportunity to buy in at lower levels. This creates an opportunity cost, the necessity to forego future opportunities that arise. If what you hold is illiquid or unmarketable, the opportunity cost increases further; the illiquidity precludes your switching to better bargains.

#15: Reasonable & Consistent Returns > Spectacular & Volatile Returns

A corollary to the importance of compounding is that it is very difficult to recover from even one large loss, which could literally destroy all at once the beneficial effects of many years of investment success.

In other words, an investor is more likely to do well by achieving consistently good returns with limited downside risk than by achieving volatile and sometimes even spectacular gains but with considerable risk of principal.

An investor who earns 16 percent annual returns over a decade, for example, will, perhaps surprisingly, end up with more money than an investor who earns 20 percent a year for nine years and then loses 15 percent the tenth year.

#16: Prepare for the Worst

Investors’ intent on avoiding loss must position themselves to survive and even prosper under any circumstances.

Bad luck can befall you; mistakes happen.

…the prudent, farsighted investor manages his or her portfolio with the knowledge that financial catastrophes can and do occur. Investors must be willing to forego some near-term return, if necessary, as an insurance premium against unexpected and unpredictable adversity.

#17: Focus on Process, Not the Outcome

Many investors mistakenly establish an investment goal of achieving a specific rate of return. Setting a goal, unfortunately, does not make that return achievable. Indeed, no matter what the goal, it may be out of reach.

Stating that you want to earn, say, 15 percent a year, does not tell you a thing about how to achieve it. Investment returns are not a direct function of how long or hard you work or how much you wish to earn. A ditch digger can work an hour of overtime for extra pay, and a piece worker earns more the more he or she produces. An investor cannot decide to think harder or put in overtime in order to achieve a higher return.

All an investor can do is follow a consistently disciplined and rigorous approach; over time the returns will come. Rather than targeting a desired rate of return, even an eminently reasonable one, investors should target risk.

#18: Wait for the Right Pitch

Warren Buffett uses a baseball analogy to articulate the discipline of value investors. A long-term-oriented value investor is a batter in a game where no balls or strikes are called, allowing dozens, even hundreds, of pitches to go by, including many at which other batters would swing.

Value investors are students of the game; they learn from every pitch, those at which they swing and those they let pass by. They are not influenced by the way others are performing; they are motivated only by their own results. They have infinite patience and are willing to wait until they are thrown a pitch they can handle-an undervalued investment opportunity.

Value investors will not invest in businesses that they cannot readily understand or ones they find excessively risky.

Most institutional investors, unlike value investors, feel compelled to be fully invested at all times. They act as if an umpire were calling balls and strikes-mostly strikes-thereby forcing them to swing at almost every pitch and forego batting selectivity for frequency.

Many individual investors, like amateur ballplayers, simply can’t distinguish a good pitch from a wild one. Both undiscriminating individuals and constrained institutional investors can take solace from knowing that most market participants feel compelled to swing just as frequently as they do.

For a value investor a pitch must not only be in the strike zone, it must be in his “sweet spot.” Results will be best when the investor is not pressured to invest prematurely. There may be times when the investor does not lift the bat from his shoulder; the cheapest security in an overvalued market may still be overvalued. You wouldn’t want to settle for an investment offering a safe 10 percent return if you thought it very likely that another offering an equally safe 15 percent return would soon materialize.

Sometimes dozens of good pitches are thrown consecutively to a value investor. In panicky markets, for example, the number of undervalued securities increases and the degree of undervaluation also grows. In buoyant markets, by contrast, both the number of undervalued securities and their degree of undervaluation declines.

When attractive opportunities are plentiful, value investors are able to sift carefully through all the bargains for the ones they find most attractive. When attractive opportunities are scarce, however, investors must exhibit great self-discipline in order to maintain the integrity of the valuation process and limit the price paid. Above all, investors must always avoid swinging at bad pitches.

#19: Complexity of Business Valuation

It would be a serious mistake to think that all the facts that describe a particular investment are or could be known. Not only may questions remain unanswered; all the right questions may not even have been asked. Even if the present could somehow be perfectly understood, most investments are dependent on outcomes that cannot be accurately foreseen.

Even if everything could be known about an investment, the complicating reality is that business values are not carved in stone. Investing would be much simpler if business values did remain constant while stock prices revolved predictably around them like the planets around the sun.

If you cannot be certain of value, after all, then how can you be certain that you are buying at a discount? The truth is that you cannot.

#20: Expecting Precision in Valuation

Many investors insist on affixing exact values to their investments, seeking precision in an imprecise world, but business value cannot be precisely determined.

Reported book value, earnings, and cash flow are, after all, only the best guesses of accountants who follow a fairly strict set of standards and practices designed more to achieve conformity than to reflect economic value. Projected results are less precise still. You cannot appraise the value of your home to the nearest thousand dollars. Why would it be any easier to place a value on vast and complex businesses?

Not only is business value imprecisely knowable, it also changes over time, fluctuating with numerous macroeconomic, microeconomic, and market-related factors. So while investors at any given time cannot determine business value with precision, they must nevertheless almost continuously reassess their estimates of value in order to incorporate all known factors that could influence their appraisal.

Any attempt to value businesses with precision will yield values that are precisely inaccurate. The problem is that it is easy to confuse the capability to make precise forecasts with the ability to make accurate ones.

Anyone with a simple, hand-held calculator can perform net present value (NPV) and internal rate of return (IRR) calculations. The advent of the computerized spreadsheet has exacerbated this problem, creating the illusion of extensive and thoughtful analysis, even for the most haphazard of efforts.

Typically, investors place a great deal of importance on the output, even though they pay little attention to the assumptions. “Garbage in, garbage out” is an apt description of the process.

In Security Analysis, Graham and David Dodd discussed the concept of a range of value – “The essential point is that security analysis does not seek to determine exactly what is the intrinsic value of a given security. It needs only to establish that the value is adequate – e.g., to protect a bond or to justify a stock purchase or else that the value is considerably higher or considerably lower than the market price. For such purposes an indefinite and approximate measure of the intrinsic value may be sufficient.”

Indeed, Graham frequently performed a calculation known as net working capital per share, a back-of-the- envelope estimate of a company’s liquidation value. His use of this rough approximation was a tacit admission that he was often unable to ascertain a company’s value more precisely.

#21: Why Margin of Safety

Value investing is the discipline of buying securities at a significant discount from their current underlying values and holding them until more of their value is realized. The element of the bargain is the key to the process.

Because investing is as much an art as a science, investors need a margin of safety. A margin of safety is achieved when securities are purchased at prices sufficiently below underlying value to allow for human error, bad luck, or extreme volatility in a complex, unpredictable, and rapidly changing world.

According to Graham, “The margin of safety is always dependent on the price paid. For any security, it will be large at one price, small at some higher price, nonexistent at some still higher price.”

Value investors seek a margin of safety, allowing room for imprecision, bad luck, or analytical error in order to avoid sizable losses over time. A margin of safety is necessary because…

• Valuation is an imprecise art

• Future is unpredictable, and

• Investors are human and do make mistakes.

#22: How Much Margin of Safety

The answer can vary from one investor to the next. How much bad luck are you willing and able to tolerate? How much volatility in business values can you absorb? What is your tolerance for error? It comes down to how much you can afford to lose.

Most investors do not seek a margin of safety in their holdings. Institutional investors who buy stocks as pieces of paper to be traded and who remain fully invested at all times fail to achieve a margin of safety. Greedy individual investors who follow market trends and fads are in the same boat.

The only margin investors who purchase Wall Street underwritings or financial-market innovations usually experience is a margin of peril.

How can investors be certain of achieving a margin of safety?

• By always buying at a significant discount to underlying business value and giving preference to tangible assets over intangibles. (This does not mean that there are not excellent investment opportunities in businesses with valuable intangible assets.)

• By replacing current holdings as better bargains come along.

• By selling when the market price of any investment comes to reflect its underlying value and by holding cash, if necessary, until other attractive investments become available.

Investors should pay attention not only to whether but also to why current holdings are undervalued.

It is critical to know why you have made an investment and to sell when the reason for owning it no longer applies. Look for investments with catalysts that may assist directly in the realization of underlying value.

Give preference to companies having good managements with a personal financial stake in the business. Finally, diversify your holdings and hedge when it is financially attractive to do so.

#23: Three Elements of Value Investing

1. Bottom-Up: Value investing employs a bottom-up strategy by which individual investment opportunities are identified one at a time through fundamental analysis. Value investors search for bargains security by security, analyzing each situation on its own merits.

The entire strategy can be concisely described as “buy a bargain and wait.” Investors must learn to assess value in order to know a bargain when they see one.

Then they must exhibit the patience and discipline to wait until a bargain emerges from their searches and buy it, regardless of the prevailing direction of the market or their own views about the economy at large.

2. Absolute-Performance Orientation: Most institutional and many individual investors have adopted a relative-performance orientation. They invest with the goal of outperforming either the market, other investors, or both and are apparently indifferent as to whether the results achieved represent an absolute gain or loss.

Good relative performance, especially short-term relative performance, is commonly sought either by imitating what others are doing or by attempting to outguess what others will do.

Value investors, by contrast, are absolute-performance oriented; they are interested in returns only insofar as they relate to the achievement of their own investment goals, not how they compare with the way the overall

market or other investors are faring. Good absolute performance is obtained by purchasing undervalued securities while selling holdings that become more fully valued. For most investors absolute returns are the only ones that really matter; you cannot, after all, spend relative performance.

Absolute-performance-oriented investors usually take a longer-term perspective than relative-performance- oriented investors. A relative-performance-oriented investor is generally unwilling or unable to tolerate long periods of underperformance and there- fore invests in whatever is currently popular. To do otherwise would jeopardize near-term results.

Relative-performance-oriented investors may actually shun situations that clearly offer attractive absolute returns over the long run if making them would risk near-term underperformance. By contrast, absolute- performance- oriented investors are likely to prefer out-of-favor holdings that may take longer to come to fruition but also carry less risk of loss.

3. Risk and Return: While most other investors are preoccupied with how much money they can make and not at all with how much they may lose, value investors focus on risk as well as return.

Risk is a perception in each investor’s mind that results from analysis of the probability and amount of potential loss from an investment. If an exploratory oil well proves to be a dry hole, it is called risky. If a bond defaults or a stock plunges in price, they are called risky.

But if the well is a gusher, the bond matures on schedule, and the stock rallies strongly, can we say they weren’t risky when the investment was made? Not at all.

The point is, in most cases no more is known about the risk of an investment after it is concluded than was known when it was made.

There are only a few things investors can do to counteract risk: diversify adequately, hedge when appropriate, and invest with a margin of safety. It is precisely because we do not and cannot know all the risks of an investment that we strive to invest at a discount. The bargain element helps to provide a cushion for when things go wrong.

#24: Overpaying for Growth

There are many investors who make decisions solely on the basis of their own forecasts of future growth. After all, the faster the earnings or cash flow of a business is growing, the greater that business’s present value. Yet several difficulties confront growth-oriented investors.

First, such investors frequently demonstrate higher confidence in their ability to predict the future than is warranted. Second, for fast-growing businesses even small differences in one’s estimate of annual growth rates can have a tremendous impact on valuation.

Moreover, with so many investors attempting to buy stock in growth companies, the prices of the consensus choices may reach levels unsupported by fundamentals.

Since entry to the “Business Hall of Fame” is frequently through a revolving door, investors may at times be lured into making overly optimistic projections based on temporarily robust results, thereby causing them to overpay for mediocre businesses.

Another difficulty with investing based on growth is that while investors tend to oversimplify growth into a single number, growth is, in fact, comprised of numerous moving parts which vary in their predictability. For any particular business, for example, earnings growth can stem from increased unit sales related to predictable

increases in the general population, to increased usage of a product by consumers, to increased market share, to greater penetration of a product into the population, or to price increases.

Warren Buffett has said, “For the investor, a too-high purchase price for the stock of an excellent company can undo the effects of a subsequent decade of favorable business developments.”

#25: Shenanigans of Growth

Investors are often overly optimistic in their assessment of the future. A good example of this is the common response to corporate write-offs.

This accounting practice enables a company at its sole discretion to clean house, instantaneously rid- ding itself of underperforming assets, uncollectible receivables, bad loans, and the costs incurred in any corporate restructuring accompanying the write-off.

Typically such moves are enthusiastically greeted by Wall Street analysts and investors alike; post-write-off the company generally reports a higher return on equity and better profit margins. Such improved results are then projected into the future, justifying a higher stock market valuation. Investors, however, should not so generously allow the slate to be wiped clean.

When historical mistakes are erased, it is too easy to view the past as error free. It is then only a small additional step to project this error-free past forward into the future, making the improbable forecast that no currently profitable operation will go sour and that no poor investments will ever again be made.

#26: Conservatism and Growth Investing

How do value investors deal with the analytical necessity to predict the unpredictable?

The only answer is conservatism. Since all projections are subject to error, optimistic ones tend to place investors on a precarious limb. Virtually everything must go right, or losses may be sustained.

Conservative forecasts can be more easily met or even exceeded. Investors are well advised to make only conservative projections and then invest only at a substantial discount from the valuations derived therefrom.

#27: How Much Research and Analysis Are Sufficient?

Some investors insist on trying to obtain perfect knowledge about their impending investments, researching companies until they think they know everything there is to know about them. They study the industry and the competition, contact former employees, industry consultants, and analysts, and become personally acquainted with top management. They analyze financial statements for the past decade and stock price trends for even longer.

This diligence is admirable, but it has two shortcomings. First, no matter how much research is performed, some information always remains elusive; investors have to learn to live with less than complete information. Second, even if an investor could know all the facts about an investment, he or she would not necessarily profit.

This is not to say that fundamental analysis is not useful. It certainly is.

But information generally follows the well-known 80/20 rule: the first 80 percent of the available information is gathered in the first 20 percent of the time spent. The value of in-depth fundamental analysis is subject to diminishing marginal returns.

Most investors strive fruitlessly for certainty and precision, avoiding situations in which information is difficult to obtain. Yet high uncertainty is frequently accompanied by low prices. By the time the uncertainty is resolved, prices are likely to have risen.

Investors frequently benefit from making investment decisions with less than perfect knowledge and are well rewarded for bearing the risk of uncertainty.

The time other investors spend delving into the last unanswered detail may cost them the chance to buy in at prices so low that they offer a margin of safety despite the incomplete information.

#28: Value Investing and Contrarian Thinking

Value investing by its very nature is contrarian. Out-of-favor securities may be undervalued; popular securities almost never are. What the herd is buying is, by definition, in favor. Securities in favor have already been bid up in price on the basis of optimistic expectations and are unlikely to represent good value that has been overlooked.

If value is not likely to exist in what the herd is buying, where may it exist? In what they are selling, unaware of, or ignoring. When the herd is selling a security, the market price may fall well beyond reason. Ignored, obscure, or newly created securities may similarly be or become undervalued.

Investors may find it difficult to act as contrarians for they can never be certain whether or when they will be proven correct. Since they are acting against the crowd, contrarians are almost always initially wrong and likely for a time to suffer paper losses. By contrast, members of the herd are nearly always right for a period. Not only are contrarians initially wrong, they may be wrong more often and for longer periods than others because market trends can continue long past any limits warranted by underlying value.

Holding a contrary opinion is not always useful to investors, however. When widely held opinions have no influence on the issue at hand, nothing is gained by swimming against the tide. It is always the consensus that the sun will rise tomorrow, but this view does not influence the outcome.

#29: Fallacy of Indexing

To value investors the concept of indexing is at best silly and at worst quite hazardous.

Warren Buffett has observed that “in any sort of a contest — financial, mental or physical — it’s an enormous advantage to have opponents who have been taught that it’s useless to even try.” I believe that over time value investors will outperform the market and that choosing to match it is both lazy and shortsighted.

Indexing is a dangerously flawed strategy for several reasons. First, it becomes self-defeating when more and more investors adopt it.

Although indexing is predicated on efficient markets, the higher the percentage of all investors who index, the more inefficient the markets become as fewer and fewer investors would be performing research and fundamental analysis.

Indeed, at the extreme, if everyone practiced indexing, stock prices would never change relative to each other because no one would be left to move them.

Another problem arises when one or more index stocks must be replaced; this occurs when a member of an index goes bankrupt or is acquired in a takeover.

Because indexers want to be fully invested in the securities that comprise the index at all times in order to match the performance of the index, the security that is added to the index as a replacement must immediately be purchased by hundreds or perhaps thousands of portfolio managers.

Owing to limited liquidity, on the day that a new stock is added to an index, it often jumps appreciably in price as indexers rush to buy. Nothing fundamental has changed; nothing makes that stock worth more today than yesterday. In effect, people are willing to pay more for that stock just because it has become part of an index.

I believe that indexing will turn out to be just another Wall Street fad. When it passes, the prices of securities included in popular indexes will almost certainly decline relative to those that have been excluded.

More significantly, as Barron’s has pointed out, “A self-reinforcing feedback loop has been created, where the success of indexing has bolstered the performance of the index itself, which, in turn promotes more indexing.”

When the market trend reverses, matching the market will not seem so attractive, the selling will then adversely affect the performance of the indexers and further exacerbate the rush for the exits.

#30: It’s a Dangerous Place

Wall Street can be a dangerous place for investors. You have no choice but to do business there, but you must always be on your guard.

The standard behavior of Wall Streeters is to pursue maximization of self-interest; the orientation is usually short term. This must be acknowledged, accepted, and dealt with. If you transact business with Wall Street with these caveats in mind, you can prosper.

If you depend on Wall Street to help you, investment success may remain elusive.

—————————————————————————————

You can also send them to the following link where they can sign up for The Safal Niveshak Post themselves and receive this Special Report for free – http://eepurl.com/cYgak

Add to favorites

Add to favorites